| < Back | Characteristics | Mastering | Next > |

| Characteristics < Back |

Mastering Next > |

While the defining traits of the Van Gelder Sound were constant over the decades, the sound evolved in ways that did not sacrifice consistency. We first begin hearing it come into form between 1952 and 1954, the first two years Van Gelder recorded professionally. The most telltale characteristic of this era is the lack of an electronic reverberation device, which makes way for the natural reverb of the Hackensack living room to be heard:

|

Al Cohn, “Jane Street”

|

Critics tend to agree that the Prospect Avenue living room had a special sonic magic. Mastering engineer Steve Hoffman, who has remastered many of Van Gelder’s recordings, shared his praise in his online forum. “Some of the Van Gelder living room recordings really take my breath away,” said Hoffman (2007), “something that sounds so good recorded so long ago. It’s amazing.” While the living room had parallel walls and floors that were not ideal for recording, Van Gelder has attributed the charm of the room’s sound in part to the high ceiling and other features like the alcove to the dining room and the hallway in the room’s northeast corner (Sidran, 1985; Clark & Cogan, 2003).

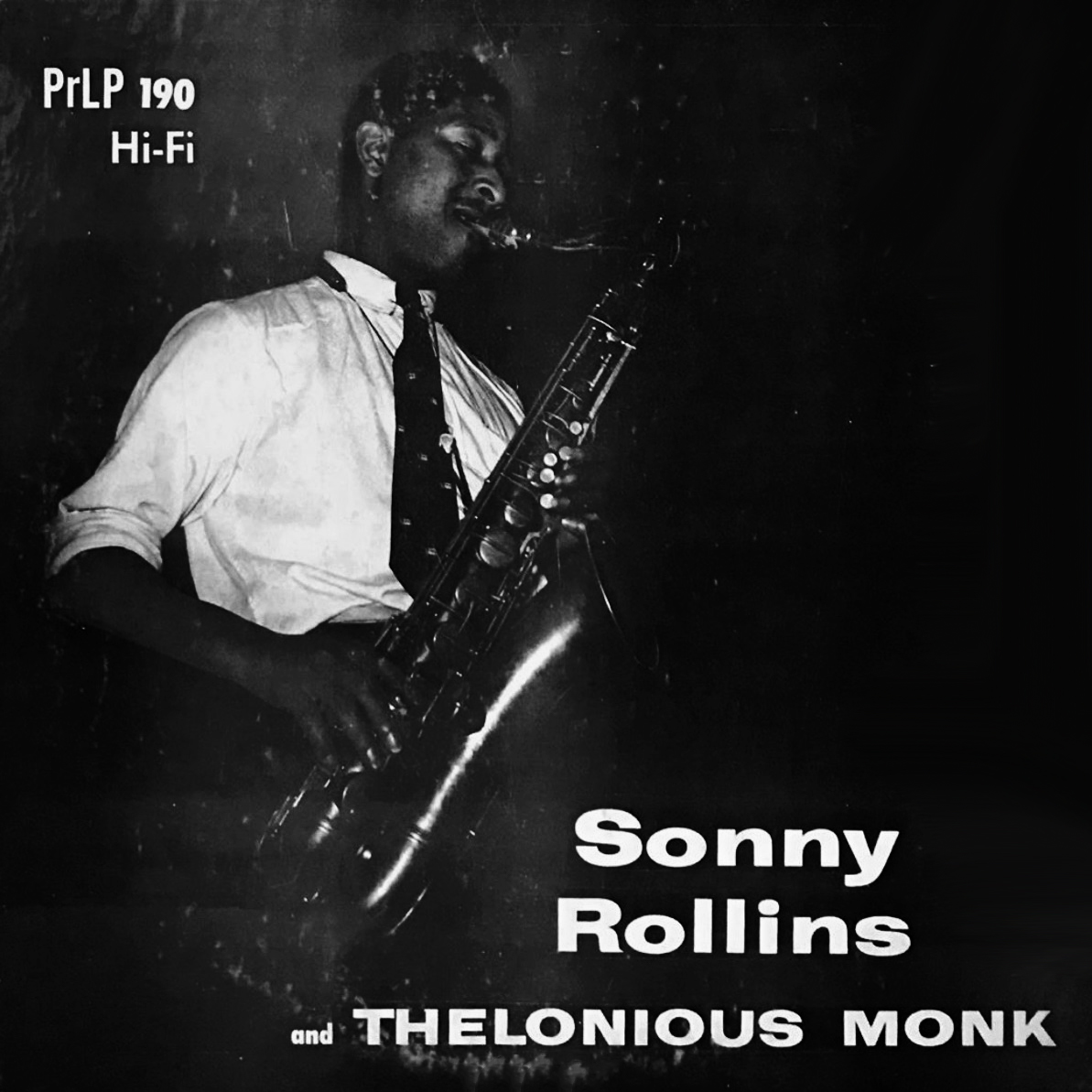

Around April 1954 the Van Gelder Sound underwent its first major transformation, at which time the effects of a new reverb unit begin creeping into the engineer’s mixes. Van Gelder always admired the sound of larger spaces like Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio in Manhattan (Cuscuna, 2004; Sickler et al., 2011), and the effect was probably implemented primarily to make the musicians he recorded sound as if they were playing in a larger space than a living room:

|

Sonny Rollins, “I Want to Be Happy”

|

But the technology wasn’t quite where it needed to be for Van Gelder to fully realize his vision. This new reverb device, which employed vibrating metal springs to imitate the reflections in a larger room, created a rather artificial sound that is easy to detect when contrasted with the living room’s natural soundstage. However, Rudy started significantly cutting back his use of the unit near the end of 1955, and by early 1956 the room sound of his mixes had returned to a much more natural state:

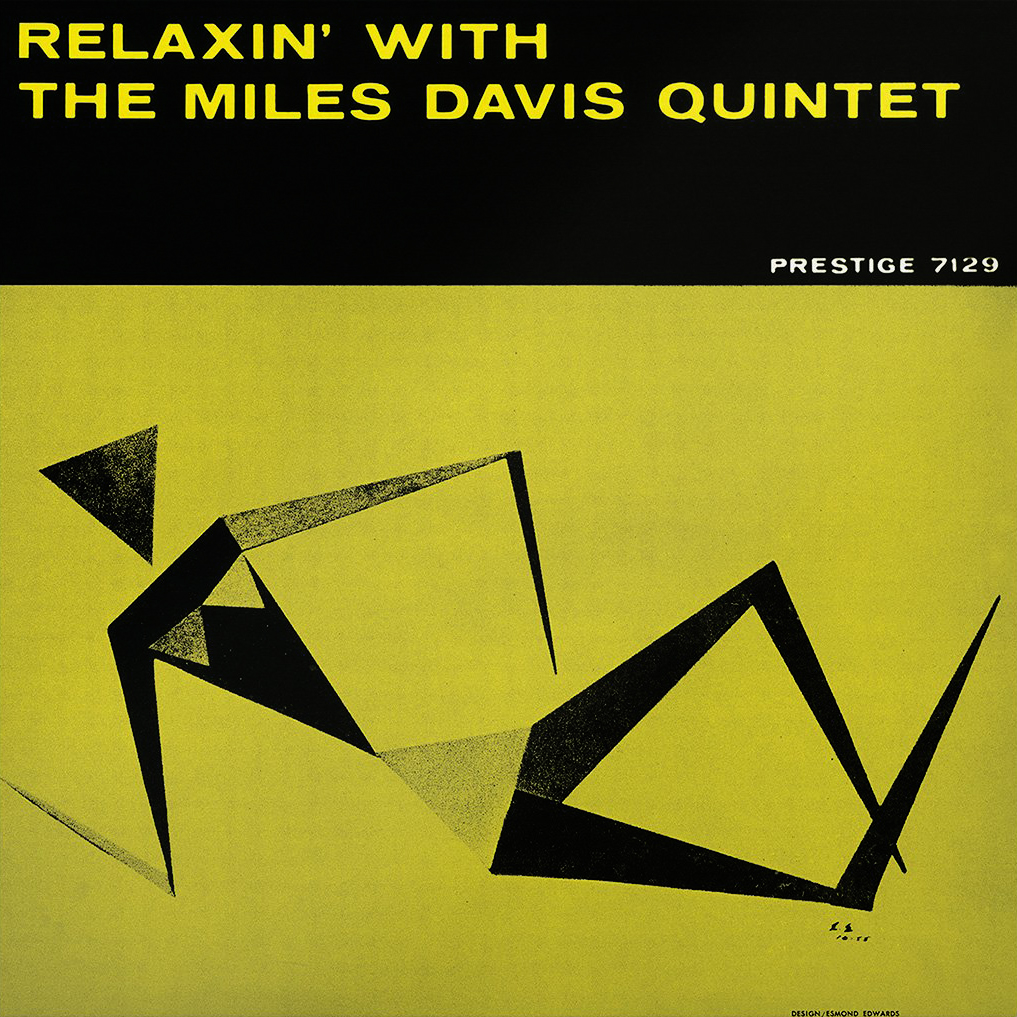

|

Miles Davis, “If I Were a Bell”

|

A Revolution in Reverb

But then in 1957, the field of artificial reverb was revolutionized by the German company Elektro-Mess-Technik or EMT. The company’s new model 140 reverb unit was light years ahead of Rudy’s old spring reverb device. It utilized a massive vibrating metal plate to create smooth, natural-sounding reflections. All in all, the unit was 7 feet long, 4 feet high, and weighed 600 pounds. Eager to make his mixes sound bigger in a less artificial way, Rudy wasted no time acquiring serial number 44 in early 1957. The rest of the music industry followed, and EMT plates eventually became staples of professional studios everywhere.

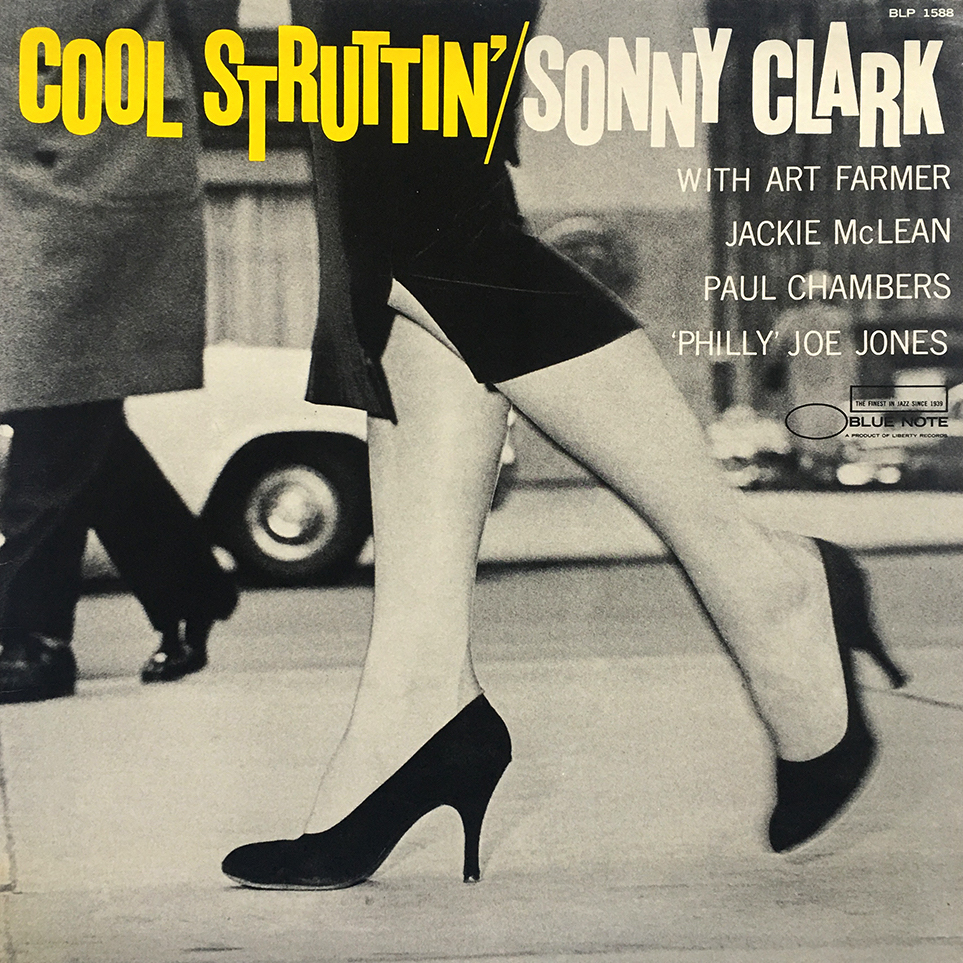

By the fall of 1957 Rudy had finally found the ideal settings for his plate reverb unit and began using it more liberally. This signified a shift from the drier small room sound Van Gelder had been getting for the past year-and-a-half to an expansive, dark soundstage more closely aligned with the larger recording spaces he admired. Rudy continued to apply the effect with much success throughout 1958, and as the Hackensack era drew to a close in early 1959 he was getting a room sound staggeringly similar to the sound he would get in the much larger live room of his next studio:

|

Sonny Clark, “Cool Struttin'”

|

The plate reverb we hear on all Van Gelder recordings between 1957 and 1961 is one-of-a-kind. Upon purchasing a second EMT 140 plate in the early ‘60s, the engineer expected a unit that sounded similar to the first, but was surprised to find that it sounded quite different. Preferring the sound of the original plate, he reached out to Wilhelm Franz, founder of EMT, to see if they could swap the new plate for one that more closely mirrored the sound of the first. In correspondence dated April 9, 1962 and after an exchange of tape recordings provided to Franz by Van Gelder, Franz explained that his engineering staff was in unanimous agreement: Van Gelder’s first plate not only sounded different, it sounded different than all one-thousand-something models they had manufactured since. Franz agreed to replace Van Gelder’s new device, though he was doubtful that it would reproduce the sound of the first. Van Gelder decided to keep the new unit and both plates remain in his studio today.

| < Back | Characteristics | Mastering | Next > |

| Characteristics < Back |

Mastering Next > |