| < Back | The German Connection | Englewood Cliffs | Next > |

| German Connection < Back |

Englewood Cliffs Next > |

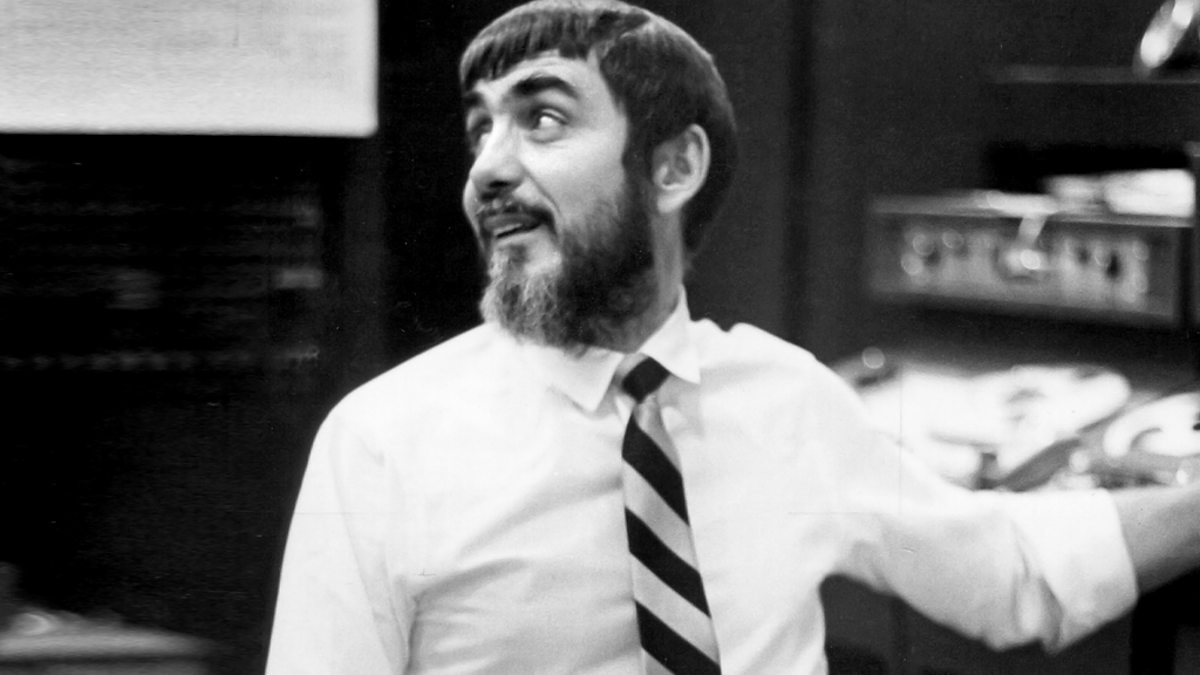

The stereo audio format is an inseparable part of listening to recorded music. This two-channel standard has been implemented on such a universal scale, the terms “stereo” and “audio system” are virtually interchangeable today in everyday language. The original theory of sound recording was a little different though. Mono, short for monaural, is the single-channel format fundamentally connected to the invention of recorded sound. Mono was the universal format engineers like Rudy Van Gelder worked with until the late 1950s when the first stereo LPs were released to the public. Stereo records and equipment gained in popularity over the years and would eventually drive the mono format to commercial extinction in the late 1960s.

Back in 1956, Van Gelder was experimenting with stereo alongside Atlantic Records engineer Tom Dowd (Zand, 2004). For several Atlantic sessions at Hackensack, Dowd brought his two-track stereo tape recorder with him. Dowd recorded the music in stereo while Van Gelder recorded it on his own equipment in mono (Kahn, 2002; Zand, 2004).

It wasn’t until March 1957 that Van Gelder made his first professional stereo recording. This Art Blakey Blue Note session took place in the ballroom of Manhattan Towers, a hotel on Broadway between 76th and 77th Streets. Van Gelder used his newly-acquired Ampex 350-2P portable two-track tape recorder for the occasion (Wolff, 1957). A few months later in May, Blue Note started recording all their sessions to both full-track (mono) and two-track (stereo) tape. However, skeptical of stereo’s staying power in the marketplace, the label wouldn’t actually release their first stereo albums to the public for two more years (Cohen, 2010).

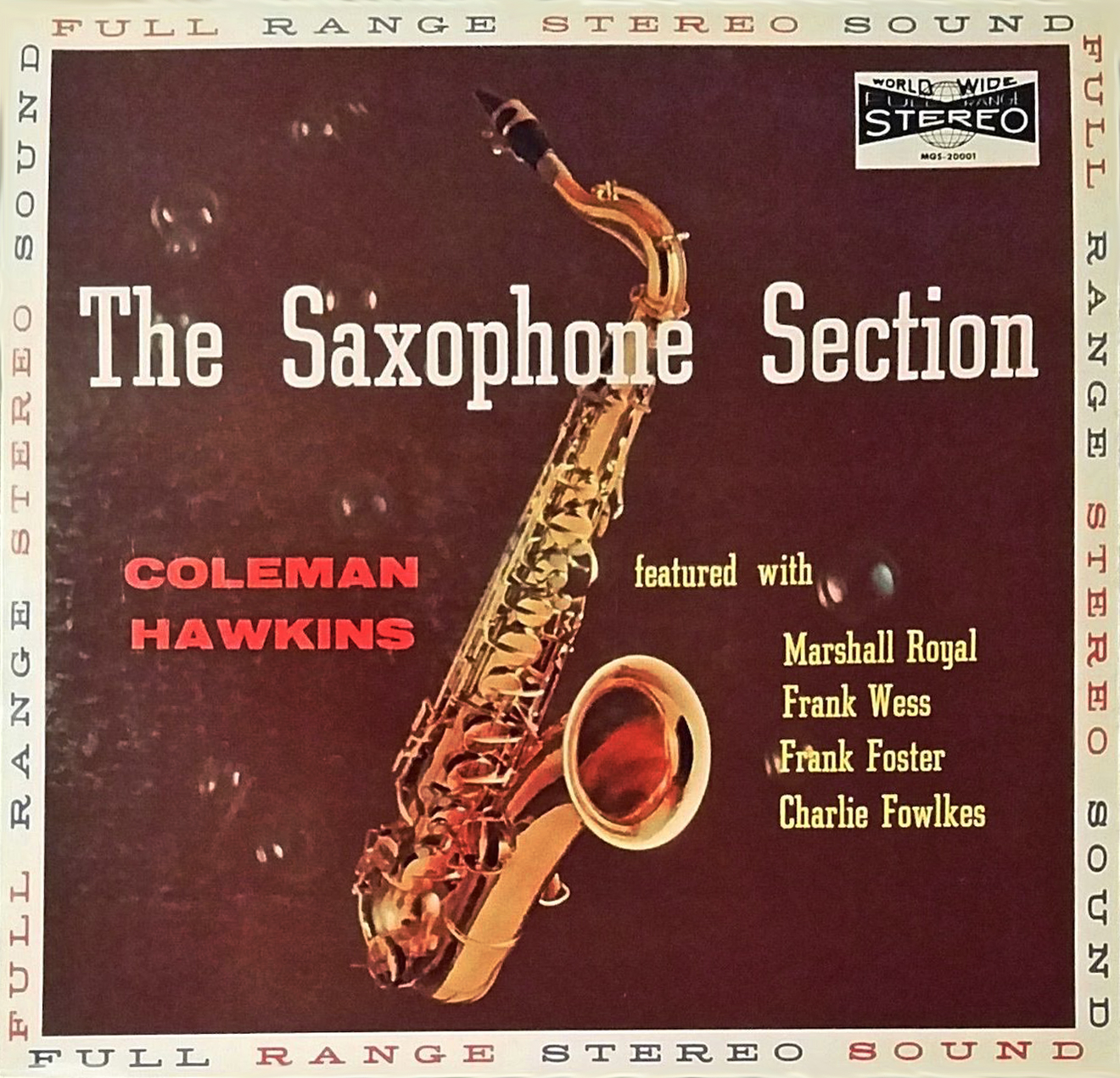

Other labels Van Gelder worked for more or less followed Blue Note’s lead when it came to stereo, but one label had different plans. By 1958 Savoy Records had been working with Van Gelder for several years. Ozzie Cadena, one of the label’s top producers, was chosen to spearhead a new stereo experiment. World Wide Records became an imprint under the Savoy label dedicated to stereo releases, and in April of that year Coleman Hawkins led a session at Hackensack that became the inaugural release for World Wide. It was also the first stereo LP to be mastered by Van Gelder with a commercial release.

|

Coleman Hawkins, “There’s Nothing Like a Dame”

|

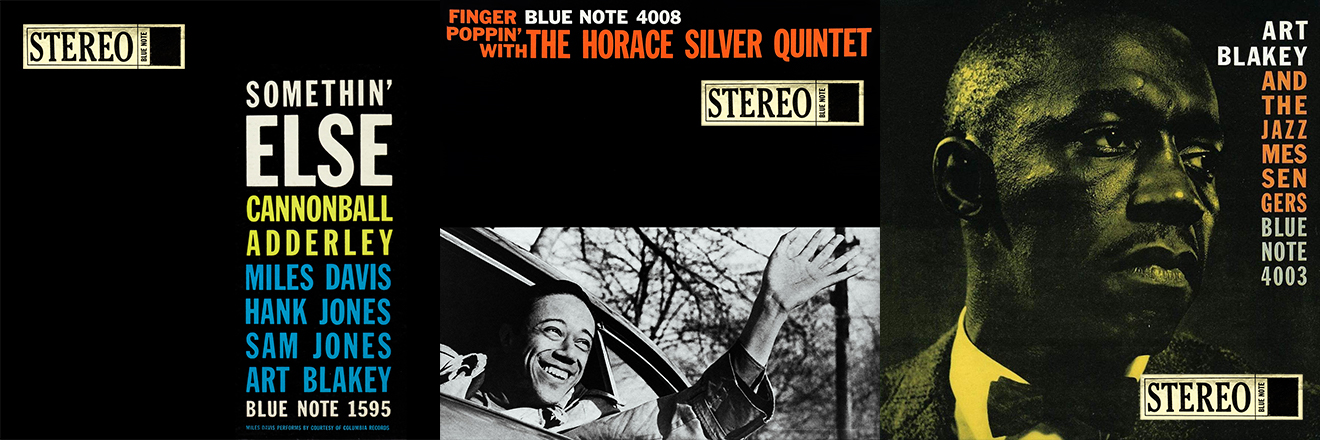

The following year, Blue Note issued their first three stereo LPs in May, all mastered by Van Gelder: Cannonball Adderely’s Somethin’ Else, Art Blakey’s Moanin’, and Finger Poppin’ with the Horace Silver Quintet. All three albums had been issued in mono several months prior, and for the next two and a half years Blue Note would continue to focus primarily on the mono format. While all albums were released in mono during this time, only albums featuring Blue Note’s most popular artists had the privilege of being issued in stereo. Even then, the release of the stereo version continued to lag several months behind the mono (Cohen, 2010).

Cannonball Adderley, “Autumn Leaves” (Stereo) | Blue Note Records, 1958

Then in December 1961, just in time for the holiday season, Art Blakey’s Mosaic became the first Blue Note album to have the mono and stereo versions released side-by-side. Over the course of the next several months, stereo releases would get closer and closer to their mono counterparts. Finally in August 1962, Blue Note began releasing all LPs in mono and stereo simultaneously, a practice that continued uninterrupted until the demise of the mono format later that decade (Cohen, 2010).

Main photo: Rudy Van Gelder’s Technics SL-1100 turntable (Photo credit: Atane Ofiaja)

| < Back | The German Connection | Englewood Cliffs | Next > |

| German Connection < Back |

Englewood Cliffs Next > |