| < Back | Mono & Stereo | Construction | Next > |

| Mono & Stereo < Back |

Construction Next > |

In the mid 1950s, Rudy Van Gelder was still practicing optometry but making a lot more money from his recording activities (Myers, 2012). He had so much work that he had to start allocating specific days of the week for specific labels (Sickler et al., 2011; Myers, 2012). Not only did this produce a steady stream of revenue, he had also been fortunate enough to witness the artistry of dozens of the world’s finest jazz musicians first-hand. Always striving for the highest level of efficiency possible, the business-savvy engineer felt there were improvements to be made, both in terms of his work and personal life.

Reasons for Moving

At the outset of 1954, Rudy was engaged. He and his fiancé, Elva, lived together in Manhattan. Back in Hackensack, Rudy’s recording business was really starting to pick up. So the couple decided to leave the city and rent a place on the same street as his parents (Myers, 2012). After tying the knot the following year, it was finally time for Rudy and Elva to find a home of their own (Murphy, 2008).

But Rudy couldn’t keep recording at his parents’ house forever, and despite having moved out several years prior, he couldn’t help but feel like he was imposing (Clark & Cogan, 2003). At one point his parents even went as far as adding an entrance to the bedroom wing of the home so they wouldn’t interrupt recording sessions (Murphy, 2008; Myers, 2012). Also pushing Rudy to relocate, Alfred Lion had always wanted to record at night, having said on numerous occasions, “Good things happen at night.” But complaints from neighbors had taken that option away quite some time ago. Then in the fall of 1957, after a series of sessions for the Prestige album Gil Evans & Ten, it became clear to Van Gelder that he needed a bigger space to better suit the needs of larger ensembles (Hovan, 1989; Zand, 2004; Murphy, 2008; Sickler et al., 2011).

The budding entrepreneur had decisions to make. One option was going to work for a recording studio in the city, but Rudy strongly valued his creative freedom (Zand, 2004; Murphy 2008). Building a new studio was a more attractive option in this sense, but it also posed tremendous financial risk. However, Alfred Lion and Blue Note, Rudy’s top client, loved the idea of a new Van Gelder Studio, and Lion assured Rudy that there would be a steady stream of revenue to look forward to from Blue Note. This proved a major motivating factor in Van Gelder deciding to build his own studio, and it only made sense for the design to include a living space for he and Elva as well (Myers, 2012).

Inspiration

The vision for the studio itself came from two specific locations Van Gelder had visited in the 1950s. During this time he took a job recording on location at Symphony Hall in Boston for Vox Records, a classical label for which he had been doing a lot of mastering work. There he spent an entire week learning the acoustics of the venue’s large performance space, and the experience made a lasting impression (Sickler et al., 2011).

The other space was Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio, which was originally a massive church (Cuscuna, 2004). Van Gelder had visited 30th Street while playing an advisory role to bandleader Larry Elgart (Skea, 2002) and he once said of the studio, “I liked virtually everything I heard out of there” (Karp, 2009). Coupled with the needs of artists like Gil Evans, Van Gelder’s preference for the sound of larger spaces had him thinking big.

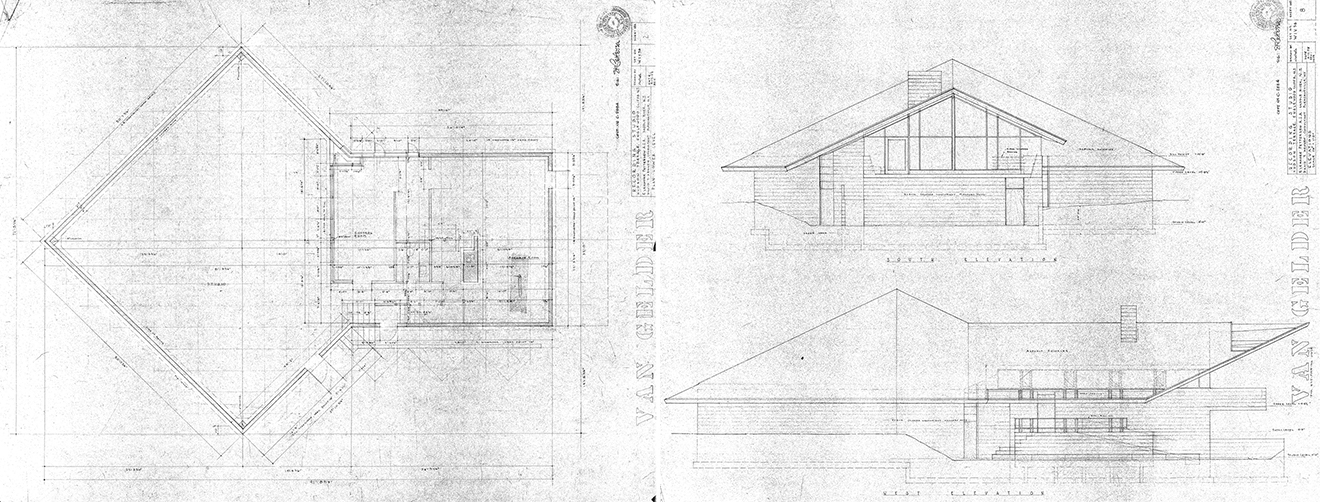

For the design of the space, both Elva and Rudy were inspired by an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that featured the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright was interested in designing homes using all organic materials, which fit with the couple’s aesthetic. But hiring Wright himself would have been expensive, so they went to David Henken, a student of Wright’s who had designed some of the homes in New York’s Usonia Homes District (Myers, 2012). No professional acousticians were hired in the design of the studio, and none of the contemporary practices for soundproofing were used (Zand, 2004).

Main photo: The ceiling of Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio (Photo credit: Atane Ofiaja)

| < Back | Mono & Stereo | Construction | Next > |

| Mono & Stereo < Back |

Construction Next > |