| < Back | The Van Gelder Sound | Visions of a Larger Soundstage | Next > |

| Van Gelder Sound Intro < Back |

Soundstage Next > |

What is it about the Van Gelder Sound that makes it so easy to identify? Rudy’s sonic recipe included four main ingredients: immediacy, low noise, a large soundstage, and an idiosyncratic piano sound.

Immediacy

First and foremost, Van Gelder used techniques including close miking, peak limiting, and tape saturation that gave the music a substantial sense of immediacy. Rudy’s role in the historical development of close miking is particularly evident. By modern standards, microphone techniques were still underdeveloped in the late 1940s. As result, only vocalists and instrumental soloists ever sounded “close” to the listener. For smaller jazz groups, this included brass, reeds, and occasionally guitar and piano. Drums and bass were universally slighted in the overall mix, leaving them sounding distant and fuzzy on most records.

It wasn’t until the early 1950s that close miking became a common practice. The technique involved each instrument being assigned their own dedicated microphone, which greatly enhanced the overall presence and realism of recordings. Not only did Rudy help popularize this new technique, he also took it a step further than other engineers by using his microphones in a way that would effectively bring the listener even closer to the musicians. This gave his recordings a strong sense of energy that remains a unique signifier of his sound to this day.

As a listener, if your relationship with a record were likened to that of an audience member at a jazz club, Rudy moved you from sitting somewhere in the middle to the front row. Producer Michael Cuscuna helps explain:

Blue Note producer Alfred Lion, one of Rudy’s earliest collaborators, also helped shape the Van Gelder Sound, especially in terms of its immediacy and presence. In particular, Lion had a vested interest in bringing the rhythm section to the fore of Blue Note’s recordings:

Because of this, and because Rudy served as Blue Note’s sole engineer for the majority of the 1950s and 1960s, the phrases “Van Gelder Sound” and “Blue Note Sound” are synonymous. Without fail, the technique was then applied by Van Gelder to all his recordings, regardless of label, making it a hallmark of the Van Gelder Sound.

|

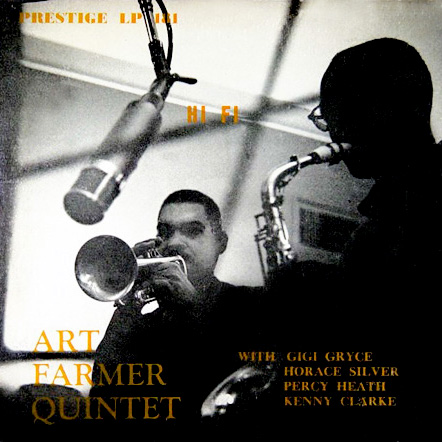

Immediacy Example

|

Low Noise

The second key element of the Van Gelder Sound is low noise. Rudy regularly demonstrated an especially strong distaste for noise throughout his career, so much that he was willing to occasionally overdrive the electronic circuits on his equipment to obtain a superior signal-to-noise ratio. This in turn would allow the music to dominate the noise floor of a recording. “Rudy recorded at a very high level in terms of decibels, or dB,” Cuscuna says. “If you listen to a Rudy Van Gelder 1955 tape, he filled it with music. […] If you listen to another ‘55 tape from Mercury or Columbia, you’ll hear a lot of tape hiss because the engineers recorded at a cautious, lower level” (Schaffer, 2010).

To achieve the lowest noise possible, Rudy regularly pushed the meter to the brink of distortion both while recording and mastering, which allowed the music to overpower tape hiss and the surface noise of vinyl LPs. The effect is seen by many to give the sound a favorable character. Recording artist Brad Allen Williams wrote in 2016, “So immediate are the recordings that even the occasional defects—the clipping distortion on the [drums], for instance—seem to become powerful signifiers of the moment and its authenticity. And when the flaws in your work become features, you are unquestionably an artist.”

|

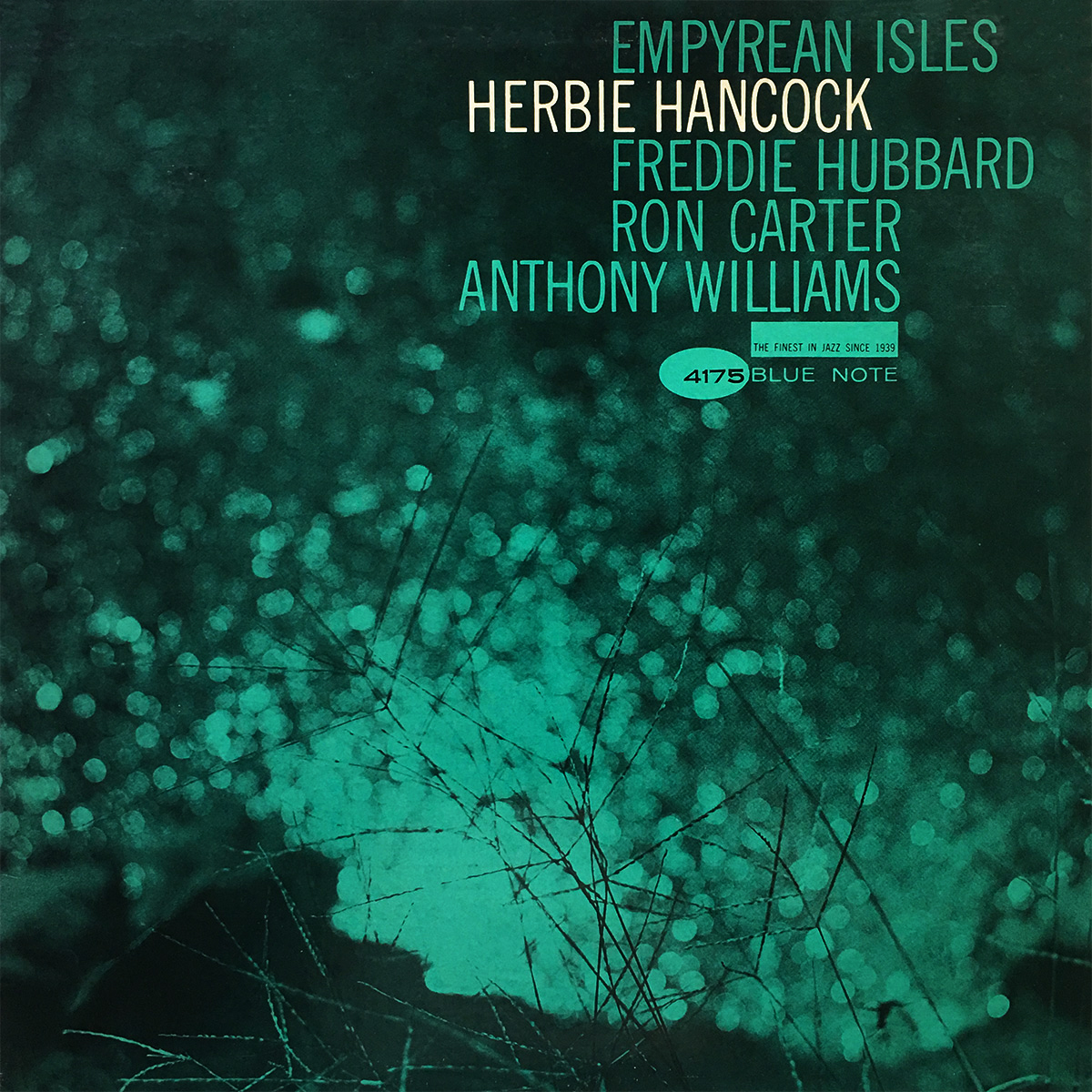

Low Noise Example

|

Soundstage

Not always, but more often than not, Van Gelder elected to sonically create a large sense of space, or soundstage, in which listeners could visualize the musicians. Sometimes soundstage is created naturally by microphones picking up the reverberations of the instruments in the room where they are played. But in many cases, the people making a record wish to make the musicians sound as if they were playing in a larger space by using either an echo chamber or artificial reverberation unit. Throughout his career, Van Gelder used artificial reverberation equipment to enhance the soundstage of his recordings.

|

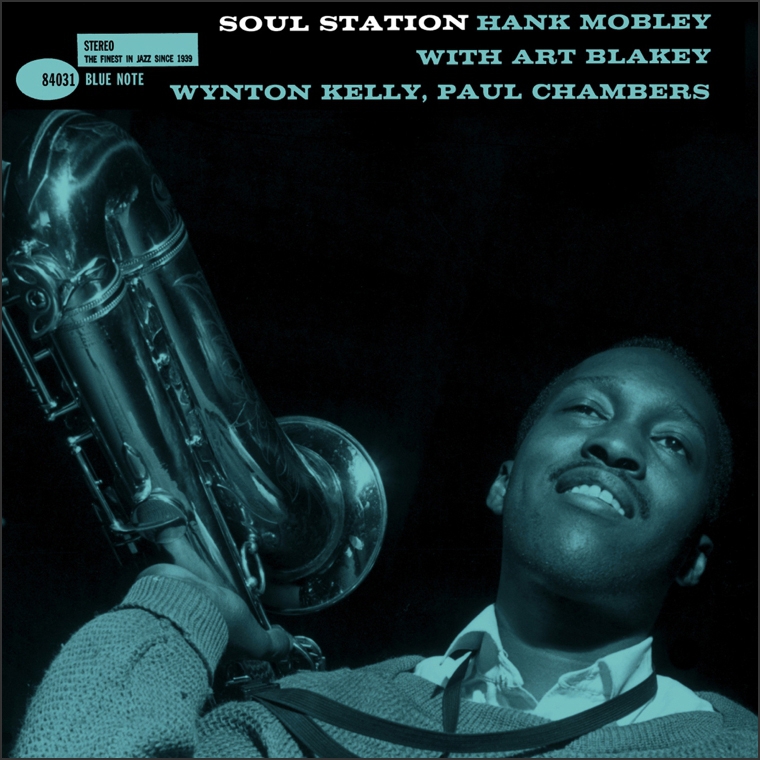

Soundstage Example

|

Piano Sound

But perhaps the most easily recognizable element of a Van Gelder mix is his piano sound. Of all the instruments in a typical jazz ensemble, the piano is the one that is most likely to give away the fact that Van Gelder engineered the recording. Dense, thick, and often called “boxy” by its critics, it is usually the most caricatured element of a Van Gelder mix.

|

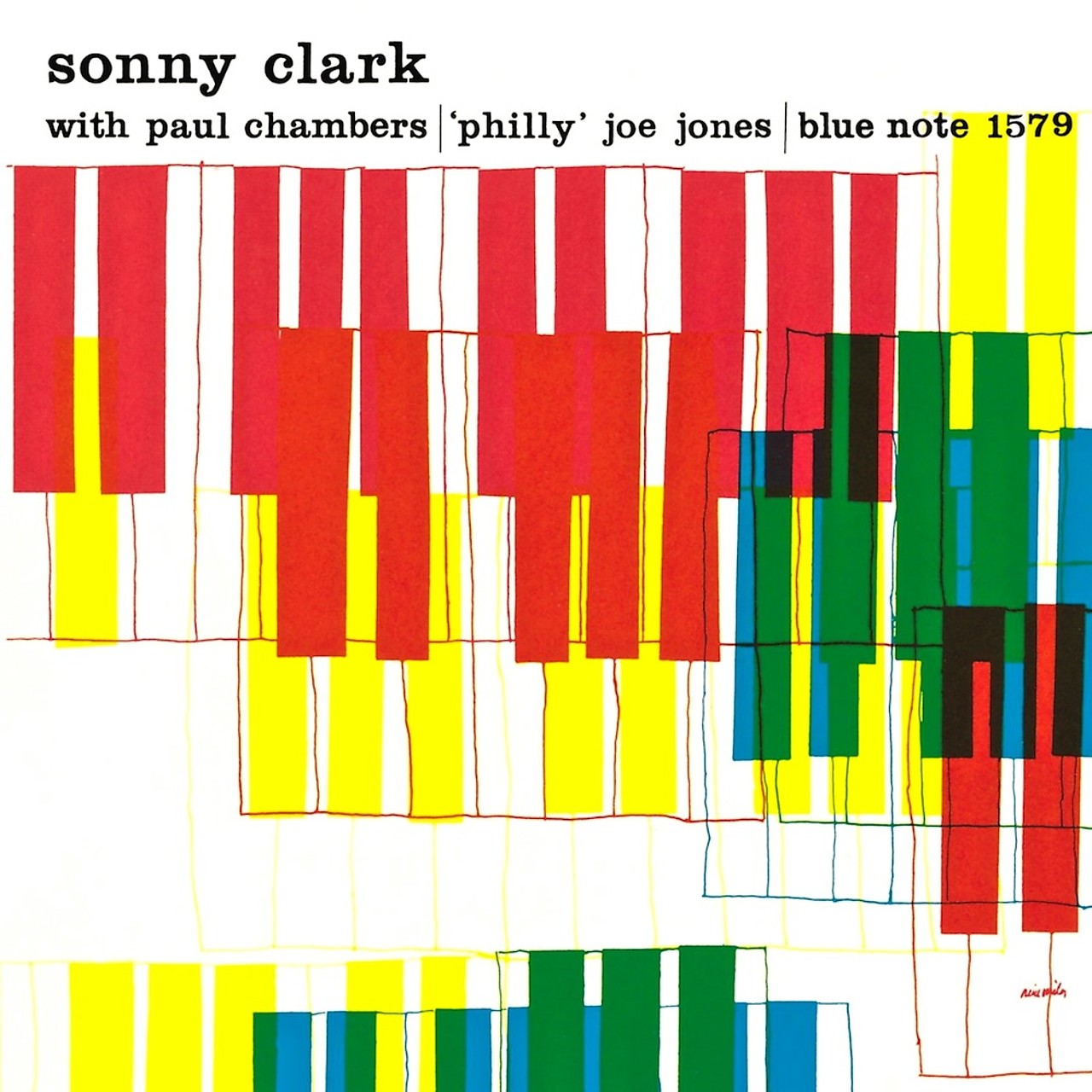

Piano Sound Example

|

Main photo: Rudy Van Gelder’s Steinway Model B grand piano (Photo credit: Atane Ofiaja)

| < Back | The Van Gelder Sound | Visions of a Larger Soundstage | Next > |

| Van Gelder Sound Intro < Back |

Soundstage Next > |