| < Back | Visions of a Larger Soundstage | The German Connection | Next > |

| Soundstage < Back |

German Connection Next > |

With the direct-to-disk recordings Rudy Van Gelder made in the 1940s, he usually handed a single acetate disk directly to each of his clients for their own personal enjoyment. These were usually one-of-a-kind 78-R.P.M. disks for which only one copy would have been made, the copy he cut during the recording process (Myers, 2012). Van Gelder also had the ability to create duplicates if his clients wanted them. However, once he started pulling in professional clients in the early 1950s, he didn’t have the equipment needed to create professional-quality master lacquer disks used by pressing plants to mass-produce the vinyl LPs sold in stores. So his clients had no choice but to have their recordings mastered elsewhere by bigger companies like RCA (Sickler et al., 2011).

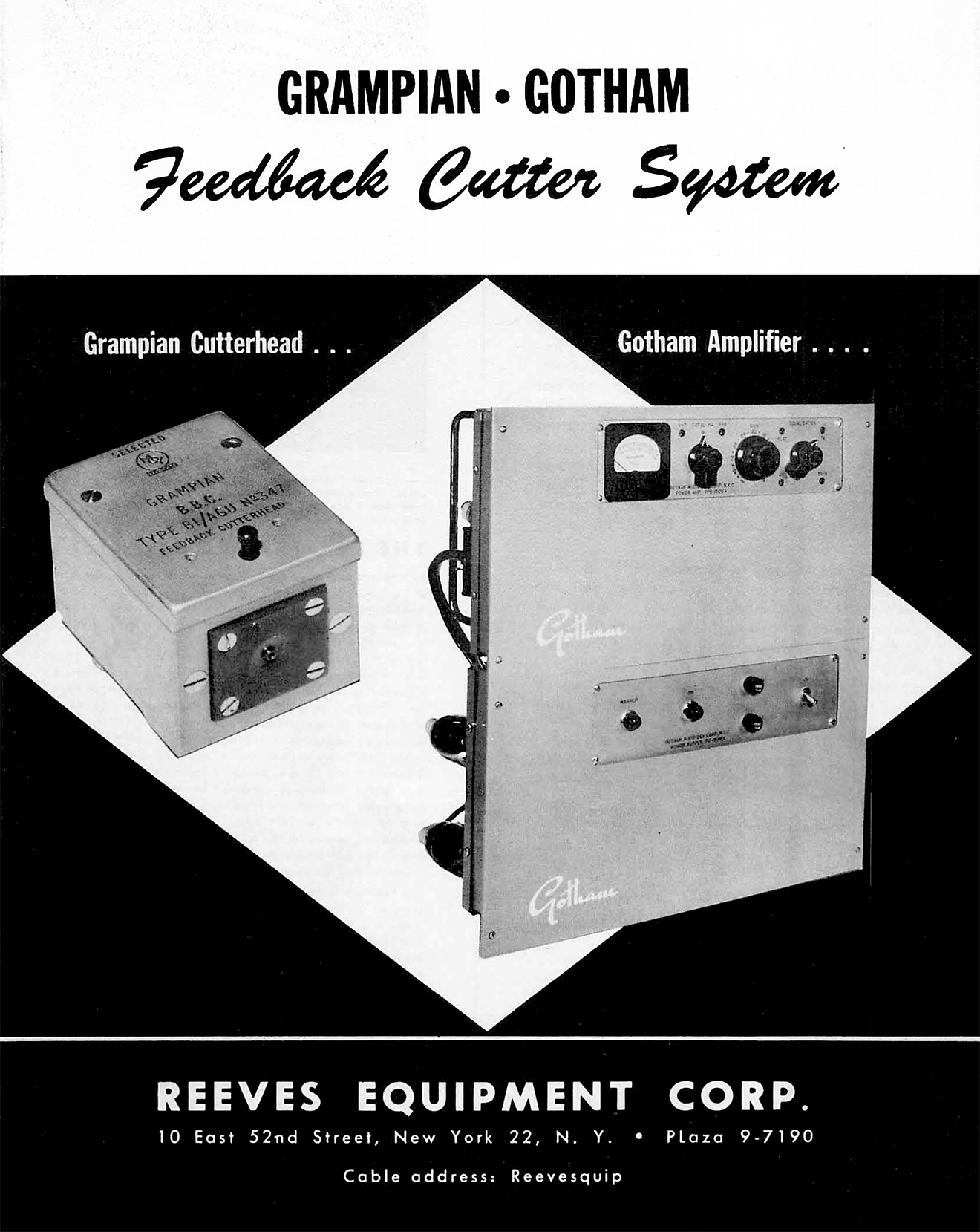

Rudy enjoyed having complete technical authority over his projects, so in 1953 he made moves to take control of the mastering process for bigger clients. That year he acquired his first professional lathe for cutting LP masters, a Fairchild 523, and paired it with a Grampian cutterhead with matching cutting amplifier. Known to meet the high standards of the British Broadcasting Corporation (Reeves Equipment Corp., 1955), the Grampian equipment was another example of Van Gelder managing to secure industry-standard gear for his personal studio.

Still, Van Gelder felt the system could be improved. Looking for a solution, he turned to Gotham Audio in Manhattan, a company known for everything from making recordings to designing and selling equipment. At Gotham, Van Gelder had a chance encounter with a staff engineer who would end up playing an important advisory role to Van Gelder for many years to come (Robertson, 1957).

A New Friend

Rein Narma was an innovative electrical engineer who immigrated from Estonia to the United States in 1951. Soon after settling in Bergenfield, New Jersey, he got a job at Gotham editing tape and recording everything from commercials to orchestras. But Narma had a deep understanding of electronics, and it didn’t take long for him to find ways to improve the commercial equipment Gotham was using (Joel, 2002). After meeting Van Gelder on the job, the two became friends and would regularly have late-night meetings at a local diner to talk shop (Sickler et al., 2011).

Van Gelder always had an idea in his head of how he wanted his LPs to sound, and in early 1954 his mastering equipment placed limitations on the finished product. Determined to find a better solution, he needed an amplifier that would allow him to cut masters louder and with greater dynamics. A more powerful amp would not only allow the music to dominate the surface noise inherent in the vinyl format, cutting his records louder would also guarantee that his clients’ records would remain competitive in jukeboxes and on the radio (Zand, 2004). Gotham agreed that Van Gelder’s idea for a cutting amplifier was both viable and marketable. Several months later, they introduced the Grampian-Gotham Feedback Cutter System in early 1955, which included an amplifier inspired by Van Gelder’s vision (Robertson, 1957).

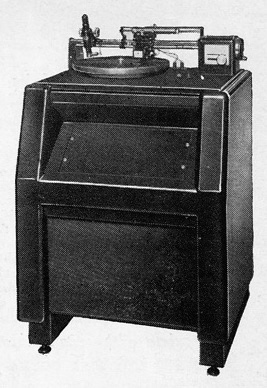

In 1955, business was booming with a capital “B”. Rudy was busy working for multiple record labels six days a week, sometimes seven, all while managing his optometry practice (Robertson, 1957). His name was showing up on countless LPs circulating in jazz circles, and he was getting more and more business from upstart labels. Now that he had a top-flight cutterhead with matching cutting amp, it only made sense to pair it with the very best lathe money could buy: the Scully model 601. Introduced that year and designed by Larry Scully in Bridgeport, Connecticut, Van Gelder was able to spend the $8,500 for the price of admission (about $80,000 in 2020) so his LP masters could benefit from the state-of-the-art machine.

Record Collecting

Rudy’s exceptional talent as a vinyl mastering engineer has not gone unnoticed by jazz record collectors, who have long shared a widespread adoration for LPs cut by Van Gelder. Original pressings are highly sought after for their sound quality, but another less obvious factor contributing to their high demand is the notion that they are works of art with Van Gelder the master artist. In an industry where the task of making a record has typically been subject to a division of labor, Rudy was always the sole technical craftsman of his LPs, from setting up the mics to preparing the masters for the pressing plant. He even signed his work like a painter, engraving his initials into the runout area of every record he cut. The unmatched care he gave to every step of this process lives on in the grooves of his records today, and it has increased the value of Van Gelder’s LPs substantially.

Main photo: Rudy Van Gelder’s Scully lathe (Photo credit: Atane Ofiaja)

| < Back | Visions of a Larger Soundstage | The German Connection | Next > |

| Soundstage < Back |

German Connection Next > |