| < Back | Updates to the Van Gelder Sound | Personal Approach | Next > |

| Updates to VG Sound < Back |

Personal Approach Next > |

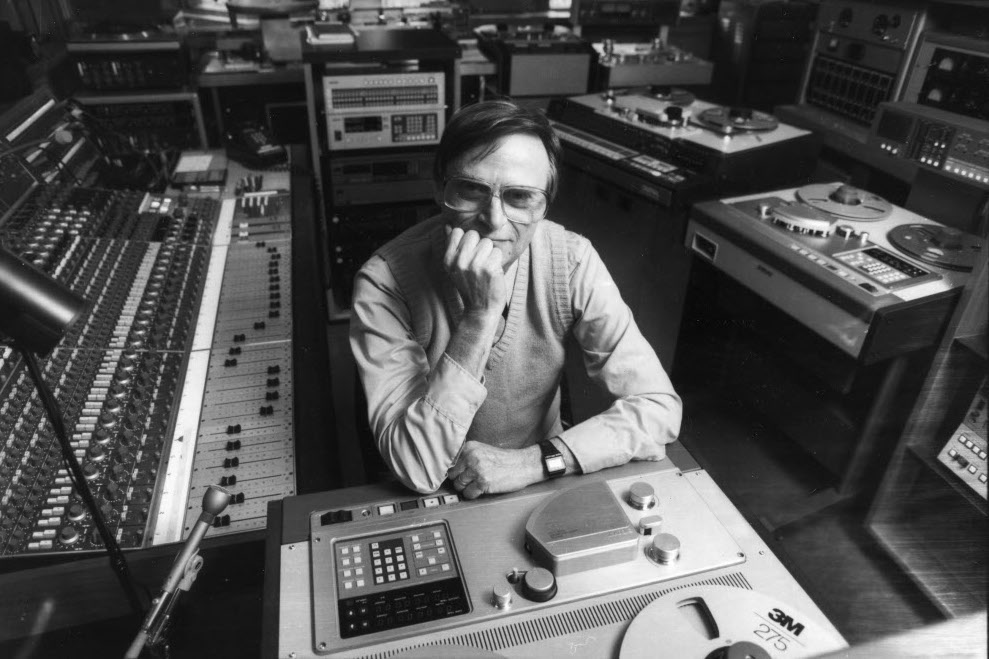

Moving into the 1970s, Van Gelder continued working with analog media including tape for recording sessions and lacquer disks for vinyl mastering. It wasn’t until the early 1980s that digital recording technology became readily available for use in recording studios. Rudy eagerly acquired his first digital recording equipment then, a Sony PCM-1630 digital tape machine with matching U-MATIC transport (Zand, 2004). The setup used videocassette tapes to capture the pulsating signals containing digital information. Rudy used the machine for mastering, and the PCM-1630 would go on to become a staple of professional mastering studios in the ‘80s and into the ‘90s.

As for capturing live music during the recording sessions, Rudy’s first digital reel-to-reel tape machine was the two-track Mitsubishi X-80, which would serve him faithfully throughout the 1980s. As the ‘90s began, Rudy acquired another digital two-track, the Sony DASH PCM-3402 (Hovan, 1989). But multitrack recording had been popular since the 1960s, and many producers and musicians preferred the higher degree of control afforded by 8, 16, and even 24-track machines. Although Rudy personally felt that multitrack recording generally did the music a disservice (Sidran, 1985; Sickler et al., 2011), he too had been using analog multitrack tape machines throughout the 1970s. To continue meeting his clients’ needs in the digital era, he acquired a digital 24-track recorder, the Sony DASH PCM-3324.

When digital audio first hit the scene in the 1980s, not everyone welcomed it with open arms. Analog enthusiasts dismissed it as sounding “cold” and “brittle”, preferring the “warmth” of tape and vinyl. However, Van Gelder was in the habit of embracing technological advances, especially if they improved his workflow. For an in-demand professional like Rudy who worked alone — six days a week at times — the efficiency and convenience of modern equipment was always attractive. “I don’t want to go back to [analog] tape,” he said in 2004. “I don’t want to go back to tubes. I don’t want to edit with a razor blade” (Clark & Cogan, 2003, p. 48). When asked what modern recording technology he wished he had in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Van Gelder replied, “All of it” (Karp, 2009). Rudy also dismissed the naysayer’s claims that digital audio formats inherently sounded inferior:

For Rudy, digital was “a total revolution in the way sound is recorded”. He added, “People really don’t understand how far-reaching that is yet. They’re comparing analog to digital but there’s no comparison. […] People ask me if I’m sentimental about the demise of the LP. Absolutely not. I’m glad to see it go” (Hovan 1989).

Van Gelder was also aware of the advantages that came along with mastering and manufacturing in the digital era:

Ironically, some younger engineers today remain unfazed by the “inconvenience” of maintaining the same vintage equipment Rudy helped popularize in the ’50s and ’60s. An additional layer of irony comes from the fact that Van Gelder has been widely praised by record collectors for his work mastering vinyl LPs. Perhaps to their horror, Van Gelder has explained with blunt honesty that he believed “the biggest distorter is the LP itself. I’ve made thousands of LP masters,” he lamented. “I used to make 17 a day, with two lathes going simultaneously, and I’m glad to see the LP go. As far as I’m concerned, good riddance. It was a constant battle trying to make the music sound the way it should” (Rozzi, 1995, p. 46).

Some of the above quotes were taken from C. Andrew Hovan’s 1989 interview with Rudy Van Gelder for Cleveland radio station WCPN. Listen to the following audio clip to hear the extended version of Rudy’s thoughts on digital recording technology:

Rudy Van Gelder on Digital Recording Technology | 1989

A New Helper

In 1986, for the first time ever, and to the amazement of those who knew him well, Rudy Van Gelder took on an assistant. Maureen Sickler had been working at the Englewood Cliffs studio alongside her husband, Don Sickler, since 1982. Don had frequented Van Gelder’s as a trumpeter, arranger, and producer for many years, and when computer-based digital equipment became more popular, Rudy asked Maureen for help improving the workflow. Over the course of the next three decades she would take on more and more responsibility, and today Maureen owns and manages Van Gelder Studio.

| < Back | Updates to the Van Gelder Sound | Personal Approach | Next > |

| Updates to VG Sound < Back |

Personal Approach Next > |